You can spend a week in Myanmar without once seeing a picture of General Than Shwe, leader of the country’s military junta. Myanmar emphatically fails to meet one’s expectations of military dictatorships. There is no cult of personality, no pomp, no parades. The soldiers you see look oily and malnourished in their ill-fitting uniforms. The junta has only adopted the drabbest and most claustrophobic trappings of dictatorship, like the snitch on every block, the enormous McMansions of the generals and their cronies, and the stilted, Soviet-style rhetoric of the government paper:

That the government is almost universally loathed by the Burmese you meet is not surprising. It provides its people with ‘no bread and no circuses’, as the writer Thein Myint-U puts it. The circus, the unifying ideology and glitz that the junta otherwise lacks, is to be found in Buddhism. Spend one week in Myanmar and you will see about 50,000 images of the Buddha (rough estimate), like this particularly smug example in a temple in Bagan:

Despite the country’s large Hindu, Muslim and Christian populations, it is Buddhism that permeates the culture. Take Shwedagon Paya, Myanmar’s holiest place and proudest monument, an enormous mountain of gold and jewels that towers above Yangon:

It's hard not to be shocked by the opulence of Shwedagon, compared to the poverty and misery that surrounds it. Yet the Burmese are deeply proud of it. A monk insisted on showing me around, pulling me over to a parapet to point out in a hushed voice the street leading up to the pagoda where the military shot down demonstrating monks in 2007, and then the next moment leading me over to the special viewing point where, at 6.30 in the evening, you can see a beam of green light shine through the enormous diamond that sits atop the pagoda, an expensive refractive effect that is meant to symbolise the beams of light that shone from the Buddha's head at the moment he attained enlightenment. This same monk was then pathetically grateful for the 2000 Kyat (2 dollars) that I gave him. Something very complicated is going on here.

Christopher Hitchens argues in God is Not Great that the West's high opinion of Buddhism is misguided, that the religion “despises the mind and the free individual,” and preaches submission and resignation. Hitchens consequently attributes the longevity of the military junta to the centrality of Buddhism to Burmese society. While this argument might have a grain of truth, it's ultimately a simplistic analysis of the complicated relationship between the state, the religion, and the Burmese people.

This little girl is all dressed up for the ceremony where she will become a monk. Her family look comfortably well-off, so she'll probably spend a few weeks with a shaven head, living in a monastery, walking the streets barefoot to beg food from shops and homes before school starts again and she can go back to normal. For hundreds and thousand of other Burmese, though, the priesthood is an escape from poverty and potential starvation. Poor children take advantage of the free monastic education the priesthood offers, and many adults who would otherwise be jobless remain in the priesthood for life. Where all state functions have disappeared except for those of coercion, control, and the provision of basic infrastructure, then Buddhism effectively becomes a de facto welfare state. Perhaps the junta realises this, and that’s why they’ve chosen to leave the structures of Buddhism in Burmese life intact. Maybe they learnt from the example of the Khmer Rouge, who, under the influence of hard-line Maoism, set about the wholesale dismantlement of Buddhism in Cambodia with disastrous results for Cambodian society. Or maybe they recognise that they have no genuine ideology of their own, and are merely cynically co-opting the country’s most powerful narrative.

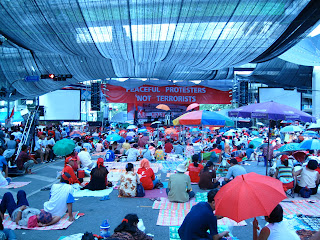

Wikipedia says that the military's eagerness to align itself with Buddhism has become a joke - people say that Burmese TV has only two colours, green and yellow, referring to the green uniforms of the military and the yellow robes of the monks. Why, then, was the monk’s rebellion of 2007 so violently crushed? That the junta was prepared to shoot monks seems to have come as a profound shock to almost everybody in Burma. But in retrospect, how could it have done otherwise? With the National League for Democracy a spent force and the frontier insurgencies calming down, it’s only Buddhism that presents any serious counterbalance to the military’s power. Had the junta not shown their willingness to shoot monks, a ‘saffron revolution’ would have been a distinct possibility. 2007 was a message to Myanmar that Buddhism will be respected and celebrated only so long as it is in harmony with the aims of the regime.

And here perhaps Hitchens’ critique is apposite. There is a powerful theme of resistance and rebellion that runs through Christianity, through Judaism, and to a lesser extent through Islam (Hinduism I don’t know). Christians can look to Jesus and Pilate, Moses and Pharaoh, David and Goliath, and all the lesser martyrs for examples of the moral imperative to resist tyranny. Buddhists have only the Buddha, sitting contentedly, eyes closed, smiling to himself. Buddhism has no obvious lessons to teach a resistance, and perhaps that’s why the junta like it so much.

Then again, Buddhism has been in Myanmar for a long time, and will still be in Myanmar long after the graves of the generals are forgotten. Perhaps this is Buddhism’s lesson for the people of Myanmar: Be patient.

Note: I don’t actually know anything about Buddhism, so if I’ve got something drastically wrong, please tell me in the comments.

-Pete